#2: Intermezzo & the Sally Rooney-verse

Is it possible to democratize literature without commodifying it?

Hi!

Welcome to The Existentialist. It's officially October, the perfect time to alternate between rewatching Gilmore Girls and reading Sally Rooney's latest. In my opinion, you're not doing fall right if your evenings can't be reduced to a cozy-core starter pack meme.

A couple of weeks ago I attended an event at Southbank Centre in London for the launch of Sally Rooney’s fourth novel, Intermezzo. Before her conversation with literary critic Merve Emre, she delivered a statement condemning the Israeli occupation of Palestine and the deaths of civilians in Israel, in Lebanon, and in Palestine. As Emre notes in her preface of the transcript of their conversation in The Paris Review, Rooney’s words served as a reminder of the importance of not isolating discussions of the novel from broader contexts.

On the off chance that you aren’t much for books, or more generously, live your life less online than us Normal People, you’re probably aware of the onslaught of discourse the book spawned online even before it was released to the public. If not, here’s a round up courtesy of

and her Substack, Deez Links, so you can get caught up before I toss my bucket hat into the swag pile.Over 900 people gathered for the event: a stylish and refreshingly effervescent sort, evidently not above material pleasures, unlike the literati I’d grown accustomed to on any given night in New York. There were bespectacled men carrying tote bags, women with Marianne-style bangs, and even a newborn, clearly destined for a future of very fine literary tastes. The event was so popular that there were streaming events for people who couldn’t snag a ticket where I pictured more of these stylish, literary types. There were also billboards (billboards!!!) for the novel and midnight release parties. It’s hard to make a tit for tat comparison to the release of Rooney’s last novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You, since I was living in Toronto at the time, but London is historically a top tier literary city and closer to Castlebar, Ireland, where Rooney is from. Even so, the frenzy for Intermezzo felt unprecedented — for Rooney, and for literary fiction in general.

All of this fandom produced its own lane of criticism. Many writers and critics have shared their derision surrounding the craze, specifically how advanced copies have become a sort of commodity meant to signify status, a coolness. Rooney herself has spoken about her discomfort with the fame her books have afforded her and even writes about the commodification of the contemporary novel in Normal People. When Connell attends a reading from a visiting writer at his university, “[h]e knows that a lot of the literary people in college see books primarily as a way of appearing cultured” and that the event “was culture as class performance, literature fetishized for its ability to take educated people on false emotional journeys. . .”

I understand this frustration. As someone with tremendous respect for Sally Rooney as a writer and for the novel as a form, someone who has made sacrifices to pursue art-making, the idea of Intermezzo as a contemporary status symbol à la The Row’s Margaux bag feels personally insulting. But then: doesn’t a person’s favorite book tell you more about them than their favorite handbag? A book can suggest a rich interior life, but attempting to externalize that interiority can feel performative and disingenuous.

In her delightful essay “why everyone wants to be the internet’s librarian,”

dubbed this phenomenon “aesthetic intellectualism.” She supposes that in a world where physical beauty has become much more attainable thanks to “looksmaxing,” society’s hottest new commodity is intellectualism. My cousin and I have a phrase we like to toss around *sarcastically* to determine if something difficult is worth doing: if it doesn’t make you hotter, don’t bother. Reading, it seems, has become a sanctioned hot-girl activity.Books, therefore, are being pulled into a superficial tradition of perception building. Of course, you can be hot and smart, so the idea that a public person known for their face or body can’t also be literary, is dubious, often sexist logic.

Even still, the idea that books are used as props, in order to further the agendas of people who actually have no regard for them annoys me. Paparazzi photos of celebrities with niche, acclaimed paperbacks are everywhere, sometimes allegedly being selected by book stylists to shape their public image. It seems, too, that more and more celebrities and influencers are starting book clubs. Whether this love for literature is genuine or part of a publicity exercise is irrelevant if you focus on the outcomes: many authors have said this kind of press has had a life-changing impact on their previously precarious book sales. So, if the death of the author has turned into the rise of the celebrity or influencer, then in an industry as financially fragile as publishing, perhaps all press is good press.

Yet, unlike being hot or stylish, which has a clearer path to attainment, being intellectual is more amorphous, more elusive. And despite the relative affordability of books and the existence of libraries, there’s an elitism inherent in the book industry and in literary circles in general. Books are cheaper than Botox, but you can have all the money in the world, and you still can’t buy intellect. This exclusionary aspect of literature is what keeps it so mysterious and coveted. Of course, gatekeeping has its place: it upholds a kind of intellectual rigor, it shows us how time, effort, and dedication can beget insight. In many ways, being intellectual (whatever that even means) is the most inaccessible cultural capital of them all.

Is it possible to democratize literature without commodifying it?

In an article on the art of decision-making for The New Yorker, Joshua Rothman argues that our life choices aren’t just about what you want to do; they’re about who you want to be. If celebrities are making reading seem glamorous, does it matter if it results in more readers? I’m disgusted by the idea that the novel is becoming a signifier of social class and simultaneously grateful that literary novels are gaining traction. Maybe you can come to reading for superficial reasons, but surely this can be a gateway drug to genuine enjoyment.

Admittedly, I love and take aestheticized shelfies, but this does not compromise my sincere love for books. Surely, these aspects of my personality can co-exist. You can have reverence for something whilst still using it to tell a story about yourself. The life of an author is notoriously difficult and unsustainable, but perhaps the desire to push back on the commodification of books, to protect them rather than squeeze them for profit, is paradoxically contributing to the precarity of the industry rather than preserving the integrity of the novel. We don’t bat an eye when musicians drop merch and yet the Intermezzo tote bags and other palpable marketing efforts have been the subject of so much scrutiny. I wonder: why do we hold books to an impossible, puristic standard compared with say, music? To engage with a novel already demands more: the burden is higher on the reader than the listener. Reading always requires more focus and often requires pre-existing knowledge. If the barrier to entry is already higher, could there be a benefit to strategically lowering the bar?

The duality of the Rooney-verse

In a recent essay for Vulture, Andrea Long Chu writes that when critics say that Rooney merely writes romance novels, they are not just accusing Rooney of unseriousness; they are also accusing her books of being commodities. For Chu, “the novel form and the commodity form are dialectically entwined, to the point that a given novel’s literary qualities may be impossible to distinguish from its economic ones.”

Rooney herself speaks to the complications of this duality in a 2019 interview with Hazlitt. She says: “If the book is turning a profit for shareholders, then the book cannot meaningfully be critiquing the system by which that profit is turned.” Still, Rooney acknowledges that there’s the possibility that there’s something in the novel that, despite being steeped in a broader political system, “transcends the transaction of simply paying for a book and owning it as a commodity” and which can “bring us a joy or a pleasure that we can salvage.” I appreciate this hopefulness, this optimism which, in my view, permeates all of Rooney’s work. Besides, without radical changes to our current system in which everything is bought and sold for capital, how else are we to disseminate literature to the broader public and compensate writers for their work?

I agree with Chu and Rooney, but the criticisms calling Rooney’s work “unserious" as well as the collective interest in her personhood, is obviously augmented by the fact that her work is both critically and commercially successful. That is to say, her work is, on the whole, thought of as a meaningful dialectic whilst being commercially successful — a rare feat for literary fiction. This is worth analyzing. Yet, many assertions that her novels are “unserious” or lacking in literary merit undoubtedly has to do with the fact that she is a young woman, and one whose primary subject is love.

Relatedly, a sizable portion of the disdain surrounding Rooney’s work has to do with the approachability and resonance of her prose. In this regard, the accessibility of her novels take something as insular and elitist as literature and magically, wondrously democratizes it. This is because Rooney’s novels offer so many openings, so many ways in, without compromising the intelligence and nuance of the ideas therein. In a 2017 conversation with Michael Nolan in Tangerine Magazine, she addresses the ways in which Conversations With Friends maintains its readability despite being about theory and politics, hypothesizing that the novel is in an “awkward position between being quite an accessible read, and also having a heritage of influence that’s not necessarily so accessible.”

Take, for instance, Beautiful World, Where Are You: you might relate to the spare depictions of technology or the ritualistic descriptions of modern courtship while feeling dizzied by the digressive, existential email exchanges between the two protagonists. Or, Conversations With Friends: come for the steamy affair, stay for the exploration of power dynamics and love in a time of capitalism. Or, with Normal People, you can be taken by the exploration of vulnerability and class and Paul Mescal in the TV adaption. It feels relevant to mention that I saw him in East London (he was running, in his short shorts, obviously) but that’s a story for another time.

Rooney’s work contains gorgeous descriptions of intimacy, capitalism, musing on the limitations of language, lavish holidays, Marxism, sex. To return to the music analogy: the same concert can be attended by different kinds of fans. There are the ones who will dissect every lyric, excavating some kind of truth, and there are those who are happy to bop along to a melody in the company of a crowd. Like music, Rooney’s work can be enjoyed in a multitude of ways by a multitude of people. Get swept up in the will they, won’t they? or savor the deft turns of phrase, the brilliance of her metaphors, the sharpness of her interpersonal observations. Better yet, do it all.

Books as portals for community

At the beginning of the event in London, Rooney and Emre talked about the contemporary novel as extending beyond its emergence as a bourgeois form. Part of fostering this inclusivity, I think, has to do with changing the ways we talk about literary fiction rather than changing the content of the novels themselves, which rely on their specificity and depth of thought as a differentiator from other, more platitudinous forms. I believe much of why people don’t read has to do with a discovery and discussion problem. A vague endorsement from a celebrity can open up the gates and welcome newer, more populist readers. Equally, there are a plethora of BookTokers speaking about fiction in an array of registers, often in a way that feels more personalized than literary criticism. Unless you come from a kind of literary lineage like the aforementioned baby at the event, a lot of book talk can feel disorienting. For the rest of us: we have to learn to swim in shallower waters before we can dive into the deep. After all, sometimes you just want to know what’s the best tonic for heartbreak. Caring what critics have to say comes later.

This is the sort of framework for positioning literature I endeavour to employ when I teach or recommend a novel — that is, contextualizing novels in broader discourse, offering up fiction as a way of helping you court your own relational anxieties, to confront your own psychology, and to grapple with the philosophical questions that keep you up at night. Not only does this make literature more accessible, it leverages its powers as a tool for connection and community, too.

While I relish the solitary pleasures of reading, it was nice to see a book serving as a portal for community — and not just among writers and people with graduate degrees in literature (guilty!) but for anyone who is simply taken by a good story. As much as conversations about craft fascinate me, there’s something scintillating about discussing the joys, insights, and comforts of literature with someone who shares your enthusiasm for the same book. BTW, this is actually something I hope to eventually create with The Existentialist, so if it sounds appealing to you, please let me know! You can learn more about me and this newsletter here.

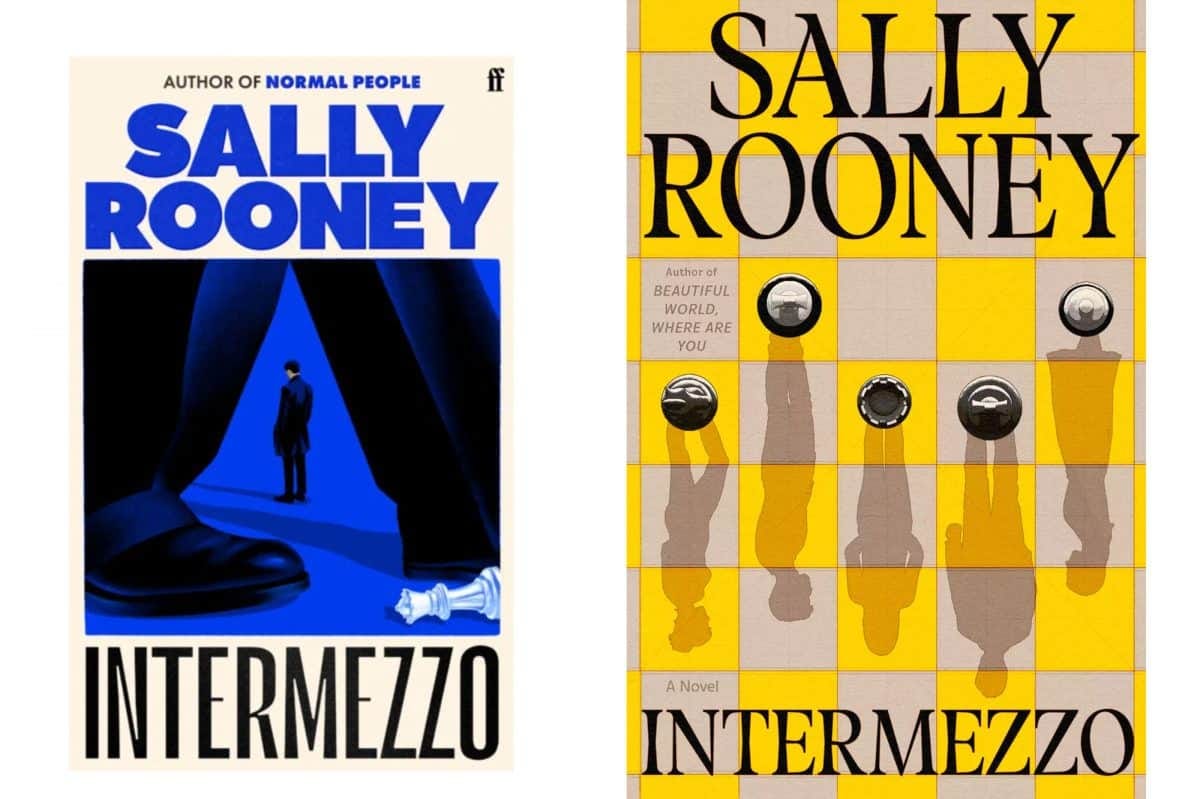

P.S. In the name of “aesthetic intellectualism,” I’m curious, which cover did you prefer?

Thanks for reading my inaugural essay! I hope you have a nice Sunday.

- Sophie

Useful essay. I am

Not a Rooney fan and found after one book I thought over stylized no need for another but she does speak to some. Thanks for help understanding her verse.

UK/Canadian version for sure